Beyond Keywords: How Semantic Search is Transforming Discovery

Originally published by EDRM and in JD Supra (2/03/2026)

By John Tredennick

Anyone who has conducted document review knows the frustration of keyword search. You craft what seems like a comprehensive list of terms, run your searches, and still miss documents you know should be there.

The numbers confirm the problem: studies consistently show that keyword search finds only 20–24% of relevant documents. That means legal teams routinely miss four out of five relevant documents despite exhaustive keyword refinement.

The reason is simple: keyword search requires exact word matching, but the same concept can be expressed countless ways. “Breach of contract,” “failure to perform,” “material default,” and “didn’t do what they promised” all mean the same thing. To a keyword system, they are completely unrelated phrases.

This creates an impossible choice. Broaden your searches to capture variations and you are overwhelmed with false positives. Narrow them for precision and you systematically miss relevant evidence. Neither serves your client well.

How Semantic Search Understands Meaning

Semantic search eliminates this dilemma by finding documents through meaning rather than word matching.

When you search for “breach of contract,” a semantic search system recognizes that documents discussing “failure to perform,” “material default,” or “non-performance of obligations” address the same legal concept—even when they share few or no keywords with your query.

This capability fundamentally changes information retrieval performance. While keyword search typically achieves 20–24% recall in ediscovery collections, semantic search implementations can achieve very high recall in recall-oriented investigations and controlled benchmarks, frequently exceeding 90% under appropriate conditions. This is not incremental improvement—it is the difference between missing most relevant documents and finding nearly all of them.

The effect is immediately intuitive to practicing lawyers. Attorneys think in concepts and legal theories, not Boolean expressions. Natural language search allows them to ask questions the way they would describe an issue to a colleague and receive documents a human reviewer would recognize as relevant.

Understanding why semantic search works requires understanding how AI systems represent and compare meaning.

In the generative AI age, this has taken on new importance. Large Language Models (LLMs) do not analyze entire document collections directly; they operate on selected subsets of information. Natural language search plays a critical upstream role by identifying the most relevant documents, passages, and evidence for LLM-based analysis. In effect, semantic search determines what information the model sees—and what it does not. The quality of downstream analysis therefore depends directly on the quality of upstream retrieval.

How AI Models Understand Language: Embeddings

An embedding is simply a representation of a concept as numbers. Since AI models run on computers, everything must be expressed numerically. What makes embeddings powerful is that they position similar concepts near each other in mathematical space.

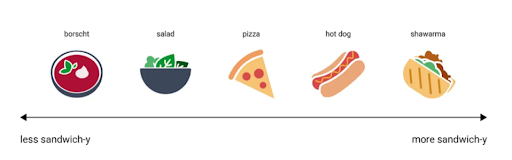

Think of it like classifying food. If you only had one dimension, you could classify items based on “sandwichness”—how sandwich-like they are. A shawarma and hot dog would score high; borscht would score low.

Figure 1: One-Dimensional Classification: The Sandwichness Spectrum. Adapted from de Gregorio, “A New DeepSeek Moment,” Medium (Jan. 2026)

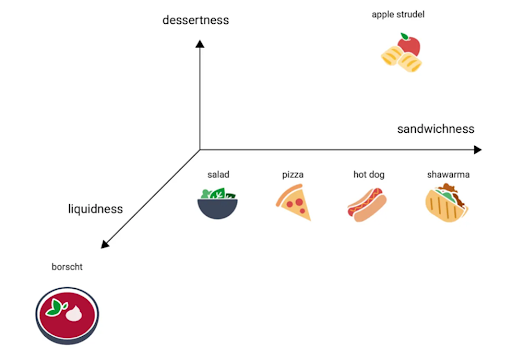

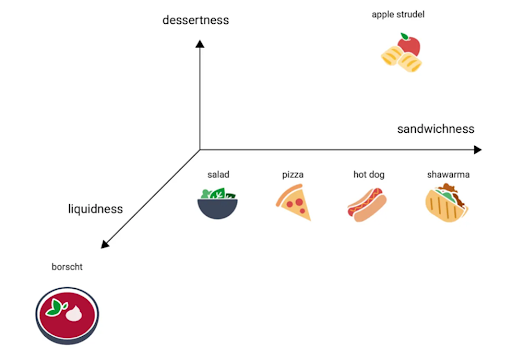

Add more dimensions and classification becomes more precise. With three dimensions—sandwichness, dessertness, and liquidness—you can now clearly distinguish apple strudel (high dessertness) from borscht (high liquidness) from pizza (neither).

Figure 2: Multi-Dimensional Classification: The Food Embedding Space. Adapted from de Gregorio, “A New DeepSeek Moment,” Medium (Jan. 2026)

The key insight is relativity. In the eyes of AI, pizza and hot dogs are more similar to each other than either is to borscht—not because the model “knows” what they taste like, but because they share similar attribute values. Similar real-world concepts have similar numerical representations.

Modern language models work the same way, just with far more dimensions—typically 768 to over 3,000. Each dimension captures some aspect of meaning. The phrase “breach of contract” gets converted into a specific pattern of numbers. So does “failure to perform.” Because they mean the same thing, their numerical patterns are nearly identical—they point in almost the same direction in this high-dimensional space.

How Embeddings Learn Meaning

These embeddings are learned, not programmed. During training, AI models process millions of documents and discover that “breach of contract” and “failure to perform” appear in similar contexts—near words like plaintiff, damages, termination, and remedy. The system figures out on its own that these phrases are related.

This learning even captures relationships between concepts. The classic example: if you take the embedding for king, subtract man, and add woman, you get something very close to queen. The model has learned that royalty and gender are separate attributes that can be combined.

Figure 3: Vector Arithmetic: King – Man + Woman = Queen. Adapted from de Gregorio, “A New DeepSeek Moment,” Medium (Jan. 2026)

This extends beyond simple synonyms. The model learns that “breach of fiduciary duty” relates to “self-dealing,” “conflict of interest,” and “loyalty obligation” because these concepts cluster together in actual legal writing. No human creates explicit rules—the relationships emerge from patterns in how language is actually used.

From Embeddings to Search

Semantic search uses this mathematical understanding of meaning to find documents.

When you enter a query, four things happen:

- Your query becomes numbers.

The phrase “Show me evidence of contract breach” gets converted into an embedding—a numerical pattern representing that concept. - Documents have already been converted.

When documents are added to the system, each gets its own embedding. This happens once, during ingestion, not during search. - The system compares patterns.

Your query embedding is compared against all document embeddings using mathematical similarity calculations. - Results reflect meaning, not words.

A document discussing “material default under the supply agreement” ranks highly even though it shares almost no keywords with “contract breach.”

This is why semantic search dramatically outperforms keyword search on recall. The system recognizes that different phrases can describe identical concepts.

Why Embeddings Are Essential

Natural language search would be computationally impossible without embeddings.

Imagine searching a collection of one million documents. Without embeddings, the system would need to read and comprehend your query, read and comprehend each document, compare meanings, and rank results. This would take hours or days.

Embeddings solve this through one-time preprocessing. Documents are converted to embeddings when they enter the system. When you search, only your query is converted—a process that takes milliseconds. The system then compares numerical patterns, completing millions of comparisons almost instantly.

Embeddings are to semantic search what indexes are to keyword search—the essential preprocessing step that makes retrieval feasible.

The Hybrid Approach: What We Do at Merlin

Semantic search transforms conceptual discovery, but certain tasks still require exact matching. Our Alchemy platform combines both approaches, capturing the strengths of each.

When keyword search excels:

- Exact citations and statutory references – finding “42 U.S.C. § 1983” requires matching that specific string

- Case numbers and docket identifiers – “Case No. 3:21-cv-00123” demands exact matching

- Boolean precision when vocabulary is known – when documents must contain specific terms

- Court-ordered keyword terms or specific contractual language

When semantic search excels:

- Conceptual queries – “Find evidence of discrimination” surfaces documents discussing “disparate treatment,” “hostile work environment,” and “retaliation” without explicit searches for each term

- Finding synonyms and paraphrased expressions

- Discovering connections between concepts that keyword search would miss

- Recall-oriented investigations where vocabulary is unknown

Our hybrid architecture processes queries through both pathways simultaneously. Keyword matching and semantic similarity operate independently, each producing ranked results. The system merges these lists, weighting documents that score well on either or both methods.

The result: comprehensive coverage that neither approach achieves alone. Documents discussing breach using formal legal language AND colloquial expressions both surface because both methods identify them as relevant.

Moving Beyond Keywords

The shift from keyword matching to semantic search represents one of the most important advances in modern discovery practice, enabling more effective use of Large Language Models for discovery analysis. Rather than forcing legal teams to anticipate every possible phrasing of an issue, semantic search allows systems to recognize conceptual relevance across different expressions. The result is not incremental improvement, but a fundamental change in how effectively relevant information can be identified in large document collections.

Embedding technology makes this possible by converting meaning into mathematics. Documents become numerical patterns that can be compared at scale. Similar meanings produce similar patterns, enabling the system to find conceptual matches regardless of vocabulary differences.

The hybrid approach recognizes that different tasks have different requirements. Combining keyword precision with semantic recall creates a system that handles the full range of discovery scenarios effectively—from exact citation lookup to broad conceptual investigation.

The question isn’t whether semantic search will transform discovery. It already has. The question is how quickly legal professionals will embrace capabilities that make systematically missing relevant documents a choice rather than an inevitability.

Learn more about Merlin Alchemy at www.merlin.tech

About the Author

John Tredennick (jt@merlin.tech) is CEO and Founder of Merlin Search Technologies, a company pioneering AI-powered document intelligence for legal professionals. A former trial lawyer and founder of Catalyst Repository Systems, he is recognized by the American Lawyer as a top six ediscovery pioneer and has been involved in legal technology and document review for more than 30 years.