NewLaw in a New Era: A Conversation about Innovation Possibilities

by John Tredennick and Lourdes Fuentes Slater

(Download the article in PDF format here.)

We got together recently to talk about the concept of NewLaw and how it relates to law firm innovation. We’ve both had a lot of experience pushing innovation for legal professionals, coming at it from different backgrounds. We thought it might be interesting to compare our perspectives and find common ground between our ideas.

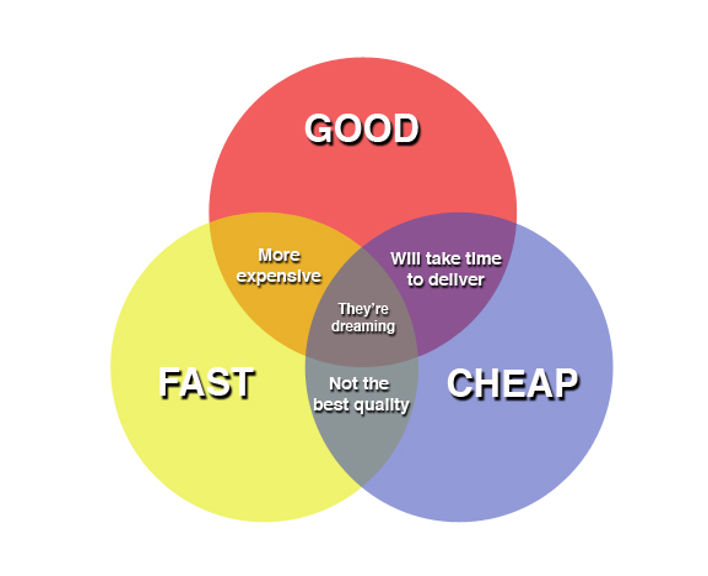

John: Back in the eighties, when I was a young associate at Holland & Hart, I would talk with my mentor, a senior partner, about ideas to innovate in our law firm. He had a business background and he brought up what he called the “Impossible Triangle.”

“What’s that?” I said. He proceeded to tell me something that every business student learns in Innovation 101. It goes like this:

- You can make it faster.

- You can make it better.

- You can make it cheaper.

The rule of the Impossible Triangle says: You can have any two of these three, but only two. You can’t have all three at the same times

Why is that?

When we were talking about legal services, the logic seemed simple enough. Back in those days we still “Shepardized” briefs, particularly as starting associates. Many of you won’t know about this but back in the day we had to look every case up in a series of books that purported to record subsequent history including reversals and later interpretations. We started with the huge annual volume to check each case but then had to go through a series of quarterly, monthly and weekly updates. And do this for each case. What a pain.

So, thinking about that chore which was in front of me at the time I realized his logic:

- We could make the process faster by putting extra associates on the job but that might increase costs.

- We could outsource this work to law students or others to cut the cost but the quality might suffer.

- We could put senior lawyers on the job to make sure they better understood subsequent rulings, but it would be slower and more expensive.

You get the idea. At least for manual legal processes, there was no obvious way to break through the impossible triangle.

I suggested this conversation, Lourdes, because I think the Impossible Triangle may not always prevail, at least not for technology-driven innovation. In this NewLaw era, I think there are cases where you can have it all—faster, better and cheaper—at the same time. We can accomplish it through process automation, using the power of networked computers to bust through this seemingly insurmountable barrier.

To use the example above, Shepard’s automated the process allowing us to check sites on the computer almost instantly. No more working through the books, far less chance to miss an update and the whole process was faster and substantially cheaper. Later, the technologists took the process to another level when they figured out how to just Shepardize the entire brief. One push of the button and the work was done. In seconds no less.

Was this a case where technology overcame the Impossible Triangle? I can say this, once we had a computerized version of Shepard’s, we associates never went back to the old, manual method, nor did we ever lament the passage of the good old days. Our clients received a better product, faster and for less cost. The Impossible Triangle suddenly seemed less than impossible.

This brings me back to the NewLaw discussion. I think NewLaw is about innovation in the legal space. I also think it is about solving previously insurmountable problems using new technology. When you combine new technologies with new ways of thinking about problems, amazing things happen and you can have all three elements of what some call the “impossible triangle.”

What’s your take?

Lourdes:

I love that you are phrasing this as NewLaw. This is the goal of legal innovation evangelists, such as myself. While, arguably, the way we “practice law” hasn’t changed very much (i.e., we still conduct investigations, do research, file motions, conduct discovery, take depositions, go to trial, etc.), the manner in which those services can be delivered has been transformed.

Technological advances now allow us to practice law more efficiently and effectively by deploying available tools. These tools should reduce costs and significantly speed up the delivery of legal services, thereby increasing the value of those services to the client.

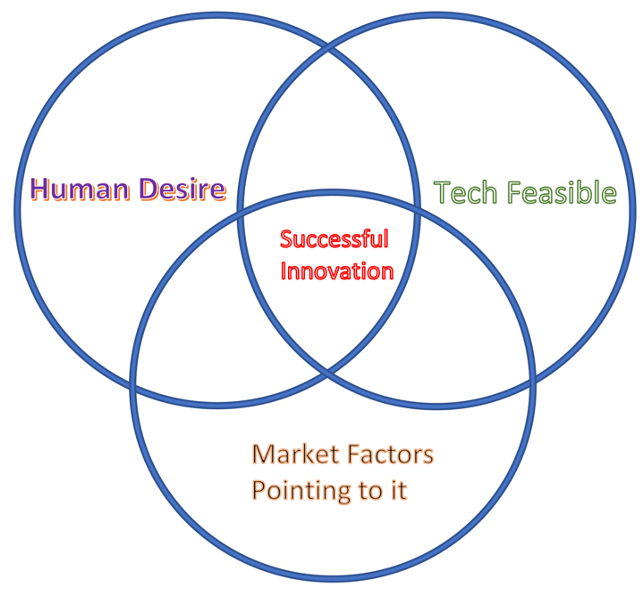

The hurdle is the lack of the perfect storm for legal innovation. That perfect storm is a combination of three elements:

- The technology solution for whatever problem or pain point you may have exists and it is feasible to acquire. Of course, we know that this element has been present for years. Indeed, we can even dare to say that technology is so far ahead of the legal industry that the legal industry cannot even see it. We have an array of legal tech tools that actually work and are not outrageously expensive.

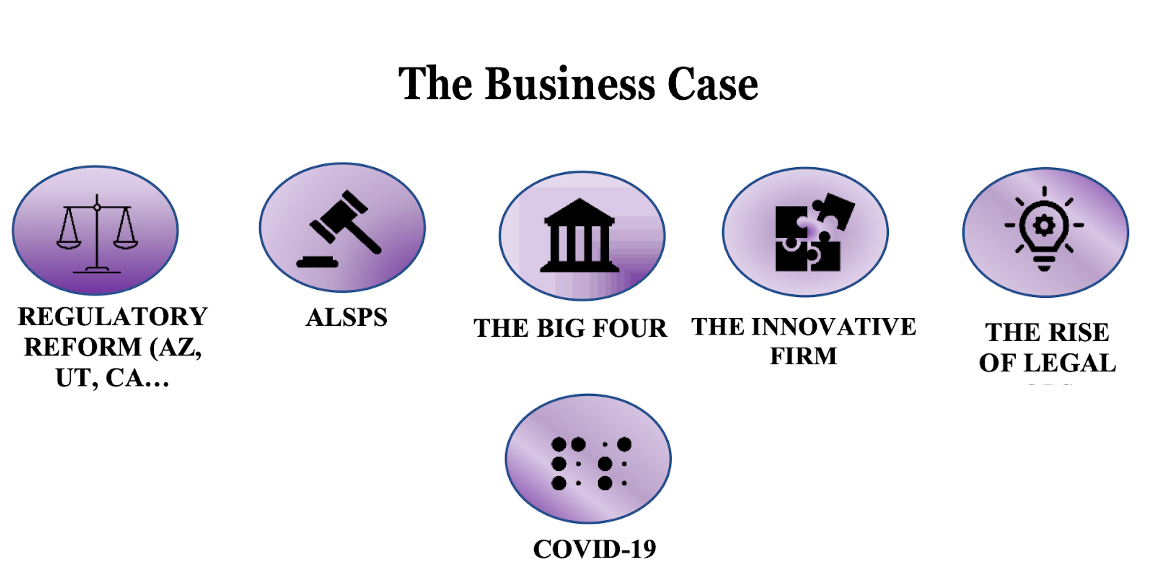

- A strong business case for innovating can be made. You need to have a business reason to pursue innovation, because we know that change management is hard. Here we get into the thorny issue of the billable hour, but for years now we have seen market factors that are pushing us to a NewLaw era. However, 2020 is a watershed moment. Both COVID-10 and the big announcements from Arizona and Utah opening the gates for non-lawyer ownership of law firms are the true tipping points for legal innovation:

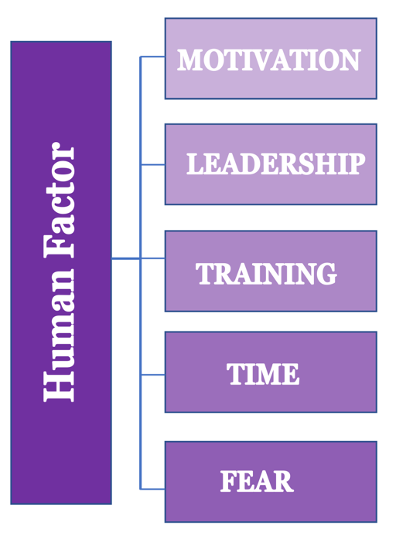

3. The above notwithstanding, we need lawyers to want to change. And that is the hardest part of our job as technology providers and innovation drivers. Because we have to deal with these factors:

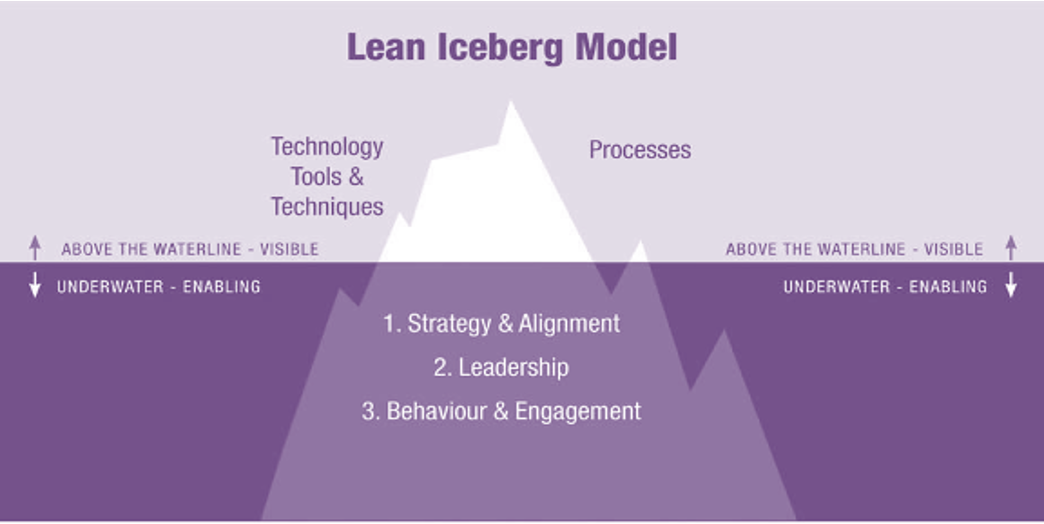

As you know, I am an advocate of Lean Six Sigma as an effective and proven approach to get us there.

The Lean Iceberg Model (adapted from Hines et al., 2008).

What are your views on how to trigger change, John? What is really going to trigger that lawyer culture change we need for the New Law to flourish? Or do you agree that we are finally in the center of that Perfect Storm.

John:

I spent twenty years in a great law firm pushing for change from the inside. (I called it guerilla leadership because I didn’t have an official position until later in my career.) I then spent another twenty pushing for change from the outside at Catalyst. I can’t say I had much success during either period of my life but I did walk away with a few conclusions which I will share here.

1. People follow incentives: The billable hour is the elephant in the room.

The biggest obstacle to change is the billable hour. When you are paid for how long you work, rather than how smart you work, you will continue employing manual, slow error prone processes. There are exceptions, of course, but the bulk of our legal professionals will not invest time and resources trying to find a better, faster, cheaper way to get the job done because it runs counter to their interests.

I don’t say this to insult lawyers. I am a proud member of the bar and respect the heck out of my colleagues. Rather, I am talking about the power of incentives. If you know compensation is a function of how many billable hours you put in, you will not be spending non-billable time trying to reduce your billables. It just doesn’t work that way for anyone, whether legal or otherwise.

So, to encourage change you have to change the incentive system. If you want an example, just look at wills and trust lawyers who charge for their services on a fixed fee basis. They were one of the first to embrace document assembly techniques because they knew if they could generate documents faster and with fewer mistakes they could reduce their costs and keep more of their fees.

2. Change usually comes from the outside (or by people trying to move up).

A second important point is that innovation almost always comes from the outside. Why is that? There are a lot of reasons but here are maybe the most important ones:

- Most big law firms are already successful, making it hard to change course. When things have been going well, it is difficult to convince your partners that good times may not continue.

- Legal professionals are consensus oriented and often work by committee. It is hard to implement radical ideas when you must first obtain consensus.

- Lawyers are risk averse. Taking a risk on an untested idea, or tossing out what has worked in the past seems risky.

- Lawyers are focused on the past. We spend our time looking at precedent rather than trying to divine the future.

- People are comfortable with established practices. Tossing out the old to try something new is not easy to do.

Most of these concerns don’t apply to outsiders, particularly those trying to gain a foothold in your market. The people who created Zoom weren’t weighed down with any of the above. Heck, they were entrepreneurs, who thrive on risk. You can’t disrupt without taking huge risks. And, there are few rewards for people who keep doing the same thing.

There is an exception to this rule. If you are a smaller firm seeking to grow (or attract larger clients), innovation may be your only option. During the past few decades, we have seen big firm lawyers break out to create boutiques based on innovative practices. Litigation boutiques implemented technology so they could match up with big firms—using smart technology to beat out the dozens of beating hearts that a big firm could throw at a problem. Likewise, business lawyers who spun out of big firms were the most likely to implement new technologies or try other methods to make their services more attractive to clients used to BigLaw engagements.

There is more to be said but, almost without exception, innovation comes from the outside or from insiders who want to bust out from the pack and have little to lose by trying something new.

3. People change when they hit a wall, but that is usually too late.

There is a third impetus for innovation. People will change their habits if they get scared. The classic story is the heart attack. When it hits you start making promises to change whatever the doctor says is the cause and often embark on those changes. Sometimes, however, you go back to your old ways.

When a firm hits a wall (declining revenues, partner defection, no business, etc.) that is a good time to talk about innovation. Fear drives people to try new things, sometimes even crazy things. Even legal professionals will consider innovation once they realize they have hit a wall. At that point change looks better than the status quo, although many people will delay hoping things get back to normal.

What does all this mean? I think you need to find people who are naturally positioned to innovate rather than hope you can persuade legal organizations to change. At every big firm you will find people with a bent toward innovation who simply need support and the knowledge that they can fail without serious repercussions. Think of these like flowers who need tending but will bloom in the right environment. Give them water, light and some nutrients and you may find a whole new garden growing at the firm.

As for the legal profession itself? Not so much. I believe the profession will continue doing what it has always done until it is pushed by outside forces to change. As you know, several states are looking at changing the rule barring outside ownership in law firms. When outsiders are allowed to step in, look for lots of innovation for all the reasons listed above. They will likely step into the less successful firms with a mission to leapfrog the top tier. They won’t accomplish that mission by trying to copy the leaders. Rather, they will change the paradigm through innovation and risk capital.

How do you get people to innovate, Lourdes?

Lourdes:

Well, for starters, I very openly address the first point you made about the perceived conflict between innovation and the billable hour. For those that tell me: “what you want me to do will make us less profitable,” I focus them on the governing court rules, fiduciary duties, and rules of professional conduct and responsibility. For me, change management starts there. It is amazing how many lawyers are NOT thinking about this. I encourage my clients to think and answer these questions:

- Who is your “client”? And, what does the client know about the ins and outs of your legal services delivery? Hint: it is not your college or law school buddy, Mrs. or Mr. J. Smith from Legal, it is the corporation or organization that retains you. So, the question becomes something along the lines of: Does your Client, the Corporation, know, for example, that you are still doing or paying for page by page document reviews, not using or deploying analytics, DMS, MMS, CMS, KM, not using AI for legal research, not project managing your cases, not providing training to your lawyers on legal tech innovation, Lean methodologies, project management, etc.? Do you have a strategic plan to up-skill your lawyers?

- Are you satisfied that you are complying with the rules of the court, your ethical duties and your professional responsibilities? By this I mean, can you act competently (includes tech competency), diligently and speedily in your representation (MRPC)? Can you ensure the just, speedy and inexpensive determination of every action and proceeding you handle (FRCP)? Can you keep your clients’ data confidential, protected from unintended disclosures, and comply with your fiduciary duties (Restatement (rHRD) of the Law Governing Lawyers, MRPC)? Are you deploying reasonable best practices in connection with all the above?

Change management is really hard and, I agree with your comments above, it almost always happens when we are forced into it. That is, when the pain of remaining the same is greater than changing, then we will change. In my career, I have been successful at innovating legal processes at law firms, but each time I had two things: 1) the full backing of the leadership and management and 2) necessity came calling.

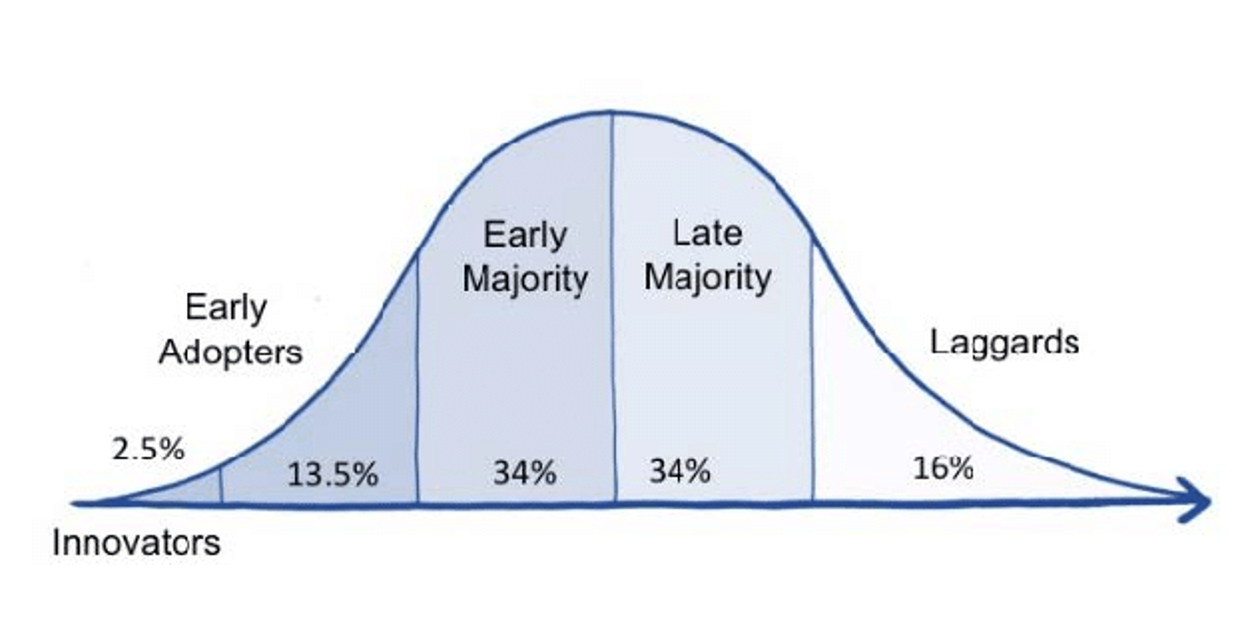

Being forced to innovate because necessity comes knocking at your door is less than optimal. Rather, my goal is to motivate lawyers to methodically and strategically plan their legal technology roadmap. Law firms today need to have a laser focus on the reality of NewLaw and the emerging landscape I discussed above. We are now looking at the pandemic and the changes in Arizona and Utah, which may open the floodgates for legal innovation through pressure to modernize from new investors. And we want to get law firms to embrace innovation. When I teach about legal innovation, I always refer to the Diffusion of Innovation (DOI) Theory, developed by E.M. Rogers. It originated in communication to explain how, over time, an idea or product gains momentum and diffuses (or spreads) through a specific population or social system. The end result of this diffusion is that people, as part of a social system, adopt a new idea, behavior, or product. Adoption of a new idea, behavior, or product (i.e., “innovation”) does not happen simultaneously in a social system; rather it is a process whereby some people are more apt to adopt the innovation than others. This is the Rogers’ Diffusion Curve:

- Innovators – These are people who want to be the first to try the innovation. They are venturesome and interested in new ideas. These people are very willing to take risks, and are often the first to develop new ideas. Very little, if anything, needs to be done to appeal to this population.

- Early Adopters – These are people who represent opinion leaders. They enjoy leadership roles, and embrace change opportunities. They are already aware of the need to change and so are very comfortable adopting new ideas. Strategies to appeal to this population include how-to manuals and information sheets on implementation. They do not need information to convince them to change.

- Early Majority – These people are rarely leaders, but they do adopt new ideas before the average person. That said, they typically need to see evidence that the innovation works before they are willing to adopt it. Strategies to appeal to this population include success stories and evidence of the innovation’s effectiveness.

- Late Majority – These people are skeptical of change, and will only adopt an innovation after it has been tried by the majority. Strategies to appeal to this population include information on how many other people have tried the innovation and have adopted it successfully.

- Laggards – These people are bound by tradition and very conservative. They are very skeptical of change and are the hardest group to bring on board. Strategies to appeal to this population include statistics, fear appeals, and pressure from people in the other adopter groups.

While recognizing that few law firms will be innovators or even early adopters, at the very least they should strive to be in the early majority. Late majority adopters and laggards face losing significant ground, clients and revenue. For an in depth discussion of innovation diffusion in law firms, I recommend this law review article by Prof. Henderson: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlr/vol122/iss2/2/.

Finding the Will and the Way

Back to your query of how do I get lawyers to innovate, I simply help clients find the will and the way to change. The “will” is the “why” of behavior change, discussed above. In contrast, the “way” refers to the cognitive and informational aspects of behavior change. The “way” is the “how” to change. How are you going to innovate your practice? Where do you start? What skills and capabilities are required? Do you have a process map ready? Both – the will and the way – are necessary for successful change management.

One of the biggest challenges is that to be able to innovate successfully you need to rewrite “old scripts.” Dennis A. Gioia, a professor of management at Penn State wrote that hidden scripts govern collective behavior, including business behavior, and they take a lot of time and effort to rewrite:

“Executives are bombarded with information. To ease the cognitive load, they rely on a set of unwritten scripts imported from the organization around them. You could even define corporate culture as a collection of scripts. Scripts are undoubtedly efficient. Managers don’t have to muddle through each new problem as fresh, (Denny) Gioia wrote, because “the mode of handling such problems has already been worked out in advance.” But therein lies the danger. Scripts can be flawed, and grow more so over time, yet they discourage active analysis.” (Emphasis added.)

Rewriting the many hidden scripts of lawyers will take executive function, time and training. It is true that behavior change will always be hard, but you can facilitate it. I am a proponent for using Lean Six Sigma as a way to facilitate change and process improvement.

Here is a readers’ digest explanation of how to use Lean to assist change management.

1. Train your team on Lean principles and tools:

The first step is to train your team on the principles of Lean Six Sigma. This does not require your team to become Lean Six Sigma certified, far from it. This is merely providing your team with a toolbox full of options for implementation of change management, many of which can be found in LSS.

2. Define, measure and analyze where you are in the Innovation Curve discussed above.

Figure out where you are in your innovation journey and where you want to be. Prioritize and identify the top 3-5 things you will work on beginning in the 1st Quarter of 2021. To help achieve this, it would be ideal to facilitate a Lean Kaizen event, which can be described as an in depth, cross-functional team meeting. In this type of event, the team will collaborate to create the right process map for your organization and your innovation goal. Through a Kaizen event, you will be able to determine if the barrier is a lack of will (not being sold on the “why”) or not knowing the “way” (lacking the know-how to get there). If the organization lacks the knowledge, skill, or capacity, you can tackle those issues one by one, as a team, and then create a process map to implement the change.

3. Take steps to Improve your legal services delivery models to make them more efficient, reducing waste.

Depending on the type of innovation you are trying to launch, tools can be identified, training can be implemented, and a path of continuous improvement can be mapped. You need to keep in mind that learning new skills, abilities, and information requires executive function and this means there is an opportunity cost to deploying the path to finding “the way.” For attorneys, this is significant because it takes time away from billable work, meeting deadlines, preparing for a pitch, writing briefs, etc. Opportunity cost is possibly the biggest challenge we have as legal professionals in trying to innovate the industry. The stakeholders and the leadership have to reduce the stress of allocating executive function to upskilling. They need to actively encourage it, actually providing incentives to upskilling.

The quest for perfection is a Lean principle but also something lawyers understand very well. It is in our DNA to seek perfection. Create a team dedicated to the continuous improvement of legal services delivery. If you are in-house, create or beef up your legal ops team. If you are in a law firm, create or beef up the team of your Chief Innovation Officer. And always communicate with everyone in the team the virtues of, and gains achieved with, innovation.

4. Continuously find ways to improve the flow of your legal services delivery models and communicate that vision to your team.

An Academy of Management Journal study found that the more leaders communicated a vision of continuity, the more it instilled a sense of cohesive organizational identity. These effects were greater when employees experienced more uncertainty at work (as measured through employee self-ratings). Leaders must communicate an appealing vision of change through emphasizing the positive – the purpose, goals, identity, and value of the employees remain, only under improved conditions.

5. Always focus on the Voice of the Client (VOC). And what the client wants is Value.

Finally, it all goes back to the client. A key Lean principle if always listening to the Voice of the Customer. Lawyers are in the service business and our clients want value. In today’s digital world, true value is provided only when delivered using the available legal technologies. There is no time like the present. Embrace this new decade with a fresh approach to your delivery of legal services. As you set your sights in 2020 and beyond, resolve to begin or continue your journey of legal process improvement to stay competitive in the NewEra of NewLaw.

John

That is great advice Lourdes. I believe we will look back and conclude that 2020 was a watershed time for change in the legal profession. Some firms and legal departments will see this as a time of great opportunity and will grow and prosper. Others may be hesitant to change what seems to be working today and risk being left behind. If this is a game of musical chairs, then the goal is to make sure you have a seat at the table when the music stops. I don’t know that everybody will in the coming years.